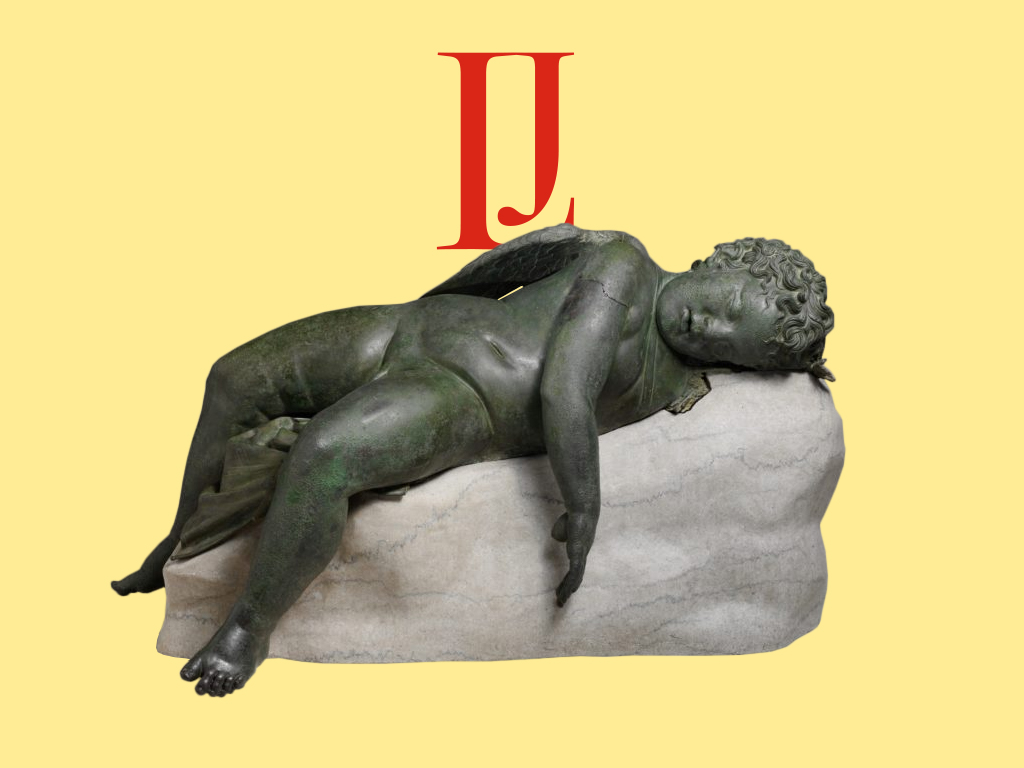

The wonderful Sappho once said, “Love, again, now, from which the limbs faint … shakes me: a sweet-bitter, irresistible creeper.” Ἔρος δηὖτέ μ’ ὀ λυσιμέλης δόνει, γλυκύπικρον ἀμάχανον ὄρπετον. Love here is a creature that crawls, slithers, sneaks up, bringing a shiver, then caving in, the inevitable surrender. Some translators of this fragment will even call it “the snake of a sweet-painful bite.” The image is strong but also intimate. It describes the trembling of love that overwhelms us, and it mostly doesn’t matter whether all the mighty love poetry will later give it wings, an arrow, a halo, or a whip. The fragment acknowledges that love can be repeated, returned, and that, the experienced warriors we are, we can recognize in it an old acquaintance.

For the eminent Croatian translator Ton Smerdel, that same fragment was “Eros, which makes the body tender, / Today it angrily tames me / That Eros fateful, bitter and sweet / that indomitable, wild beast.” Gods, wild beasts, angry taming; the heroic force piled up with some love, and the body limply tender. It’s rather like Homer, it’s not Sappho. Smerdel, as a Christian intellectual, immediately loaded both God (at least the beautiful Eros) and the somewhat frightening beast of love here. As many readers, so many small and large betrayals. Despite all of them/us, it is clear that Sappho knew well that gentle tremble that alternately burns like a nettle and caresses like a breeze, that shiver that passes through limp limbs. We know for sure that in this fragment love is precisely erotic, sexual and passionate. Greek thought arranged the faces of love precisely and eloquently. In this Sappho’s tremble we do not find a friendly philia, we do not see an unconditional parental storge, we do not feel universal agape, we are not afraid of selfish philautia … and least of all, of practical pragma. We may sense a mischievous and playful ludus, and perhaps something more: an earthquake and a collapse, the first stage of an orgasmic fractal, the expansion of a circle of trembling and silence.

If we add all those other faces to eros, we can say with Dante, that we are talking about the force that moves the Sun and other stars. Or at least about our unfulfilled dreams of that force. Unfulfilled dreaming is so human; we like to pack love and put it away in the pantry until it gets spoiled. Judeo-Christian tribal ideologues will rob us of it from above and from below, and we will wallow in fear, guilt, discomfort, and trouble. Love never dies by natural death, wrote Anaïs Nin: “It dies because we do not know how to replenish its source. It dies of blindness, error and betrayal. It dies of disease and wounds, of withering, of tarnishing.” Books have spoken and are speaking about our miserable will to tarnish, to blind love. But they also led us, like torrents of rain on dried soil, towards the renewal of its springs.

In the years of overwhelming thanatos, fear and the shiver of trepidation, this erotic tremble that the experienced Sapho talks about can still bring back some exit and relief. But it’s not just some miserable self-help and cowardly tucking in. Eros has “again, now”, a giant and daunting task. To wipe faces smeared with snot and tears, sweaty under a medical mask, to reconcile the distant poles of quarreling brothers, to calm the roar of digital noisemakers, to relax the tense limbs of rogues. In the dystopian consideration of false possibilities and lived impossibilities, love returns to Pula in one of its seemingly most innocent forms. Dictionaries see bibliophilia as valuable and wacky in one. Book-loving thieves are forgiven for stealing books at least a little faster and easier than other thieves. Mitigating circumstances are recognized: the ludus of reading, the ecstasy of words, the dread of the next chapter, the joy and sadness of the last page, sometimes disgust. True, you can still finish in trouble for some book. Sometimes, in a history that always repeats itself, they burn it, sometimes they burn you with it. The book of love is declared a general danger. Paolo and Francesca took the rap because of it, stuck in Hell, in the second circle in which the lechers suffer. Love never left them for it, though.

“That book, and he who wrote it, was a pander. That day we read no further.” The translator is rigid and his moralistic nose is slightly raised. A pander can also be a criminal being, and Dante’s “galeotto” is both more and less than that. Francesca admits to the writer that she and Paolo read the Arthurian legend of Lancelot and Guinevere who fell in love with each other with the help of Galehaut, in Italian called Galeotto. “Galeotto fu ‘l libro e chi lo scrisse.” The book and its writer were, therefore, a galeotto, a love mediator, an intermediary of love.

Like haunted lovers, people of the book sniff out the post-pandemic orders, they gather in Pula and open to the rest a happy path to love. Let the Book fair be a cheerful galeotto. Yes, it is true, in Italian, the galeotto is also a poor man doomed to paddle on a galley, a prisoner, a slave, but also a mischievous and cunning bloke. What a connection to the world of books and survival with them, from them and for them!

In the world of those that count digital “likes”, the thin gold coins that one is afraid to bite into to try them, let those famous Catullus’s kisses swarm and count in your spirit along with books and their authors: “give me, oh Lesbia basia mille, deinde centum / dein mille altera, dein secunda centum / deinde usque altera mille, deinde centum … a thousand and a hundred, then another thousand, and then another hundred kisses, and so on until, as the poem goes, the right number is confused and misplaced, so that the “envious one” (oh, smart Catullus!) never ever could discover how much did we love with books on our side, and how much we loved books. Even if we do not read further that day, we shall read in the morning, when the number is confused, when we thirstily call for waters to a tired spring.

Aljoša Pužar